Socratic Models - AI Ensembles

The period of 2018-2020 was a critical time for progress in natural language processing. On the back of Transformers, a wave of value was created with products like text completion, sentiment analysis, entity recognition, and writing improvement tools. The process for creating these technologies would be familiar to data scientists across domains: collect and label data, train and fine-tune models, test different architectures, and optimize hyperparameters.

For those close to NLP research and development, the last year has presented a clear break from this incremental progress. Large pretrained models can be prompted for answers rather than trained, single models can communicate across multiple modalities, and factual information stored in graphs and knowledge bases can augment model IQ. The economic value these innovations unlock has barely begun to be realized, and most industries haven’t felt the productivity gains.

The next wave of progress will stem from uniting several key innovations that allow for self-organizing data, detailed responses to queries, and quickly altering how machine learning systems operate. While the leap forward will come from the confluence of several synergistic technologies, I was excited by the promises offered by a recent paper titled “Socratic Models” demonstrating how real tasks could be accomplished using off-the-shelf freely available models. To see how easily such an ensemble could be deployed, I recreated pieces of their research.

Multimodal Communication

Models that unite language and image modalities have received significant attention recently, most notably CLIP and DALL-E. There are countless other multimodal models uniting speech, sound, video, and structured data, and many available with open-sourced implementations and weights. Translating between modalities is a superpower itself, but real magic can be realized by having models reason in concert with full context. When language is ambiguous, video and audio models can ground model interpretation and response using similar logic to a human thought process.

Given the quantity of research published in this field over the last few months, it’s clear that many agree with this position. Google Multisearch allows users to find content using images and text in concert, for example, asking its search engine to find socks with the same pattern as a pictured shirt. In CLIP meets GamePhysics researchers used CLIP embeddings to find scenes in video games with reported glitches from users on Reddit. Many specific applications of this technology have been prototyped, but Socratic Models is the first to offer a more general vision.

Socratic Models

Wikipedia defines the Socratic method as

a form of cooperative argumentative dialogue between individuals, based on asking and answering questions to stimulate critical thinking and to draw out ideas and underlying presuppositions.

We now have models that take different modalities of information as input (text, images, sound, spoken language) and can return text representations of their content. Through the common interface of natural language, we can have them reason, discuss, and supervise to produce higher level AI applications. This is the core idea behind Socratic Models.

While the paper discusses many ways to deploy this technology, the core methods are displayed through the interpretation of first-person (egocentric) video recording someone’s daily routine. Various pre-trained models are tasked with working together to answer questions, return search results, and summarize the day without any fine-tuning on in-domain data. A video-language model (e.g. CLIP) is asked to list objects and places seen in video stills. A large-language model (e.g. GPT-3) is prompted to provide activities that could be performed in those places and with those objects. Audio-language models (e.g. Wav2CLIP, Wav2Vec2) further supervise the likelihood that those “logs” produced are correct. This process can proceed iteratively, producing a high quality of log of what occurred in the video for summarization or question answering later.

I knew that despite the apparent simplicity of this model ensemble, it can still be a challenge to prompt the model for a specific and grounded response. To explore this space, I created a smaller version of Socratic Models combining image and language modalities.

Streamlit App

Socratic models for YouTube videos

The app all starts with a chosen video. As I default, I chose an egocentric video similar to the example in the paper, following an individual as they go through their work day. However, I tried other related videos like first person video games and unrelated like movie scenes with similar levels of success.

Frames from the video were sampled at a constant rate using OpenCV - obviously how fine-grained those samples are will affect how well the models perform. Each frame was then embedded using the CLIP image encoder and stored in a Faiss index for nearest neighbor retrieval. This enabled the simplest of the Socratic Models applications - video search.

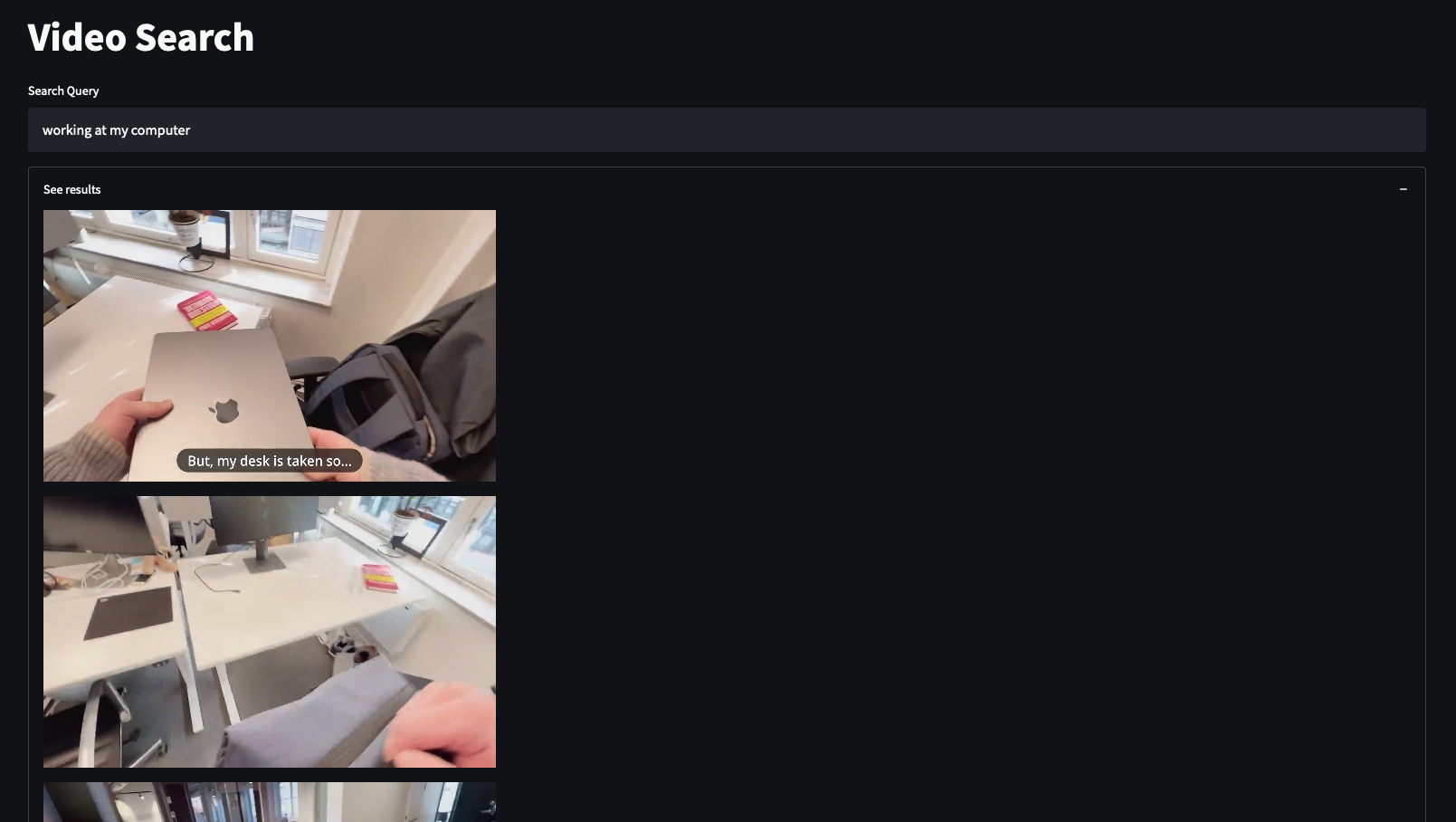

Video search for “working at my computer”

I found this application to work pretty flawlessly. The query entered into the text box is encoded using the CLIP text encoder, and a nearest neighbor search is performed in the Faiss index to find the closest image embeddings. While my queries were often simple, it was able to rank frames correctly based on semantic changes to the text, even while the same keywords were used. The only real failure mode was when I search for something not present in the sampled frames - of course, the application still returned the closest embeddings. While embedding distance could be used to threshold what was returned, model-based methods for determining relevance would likely be more robust to different types of video.

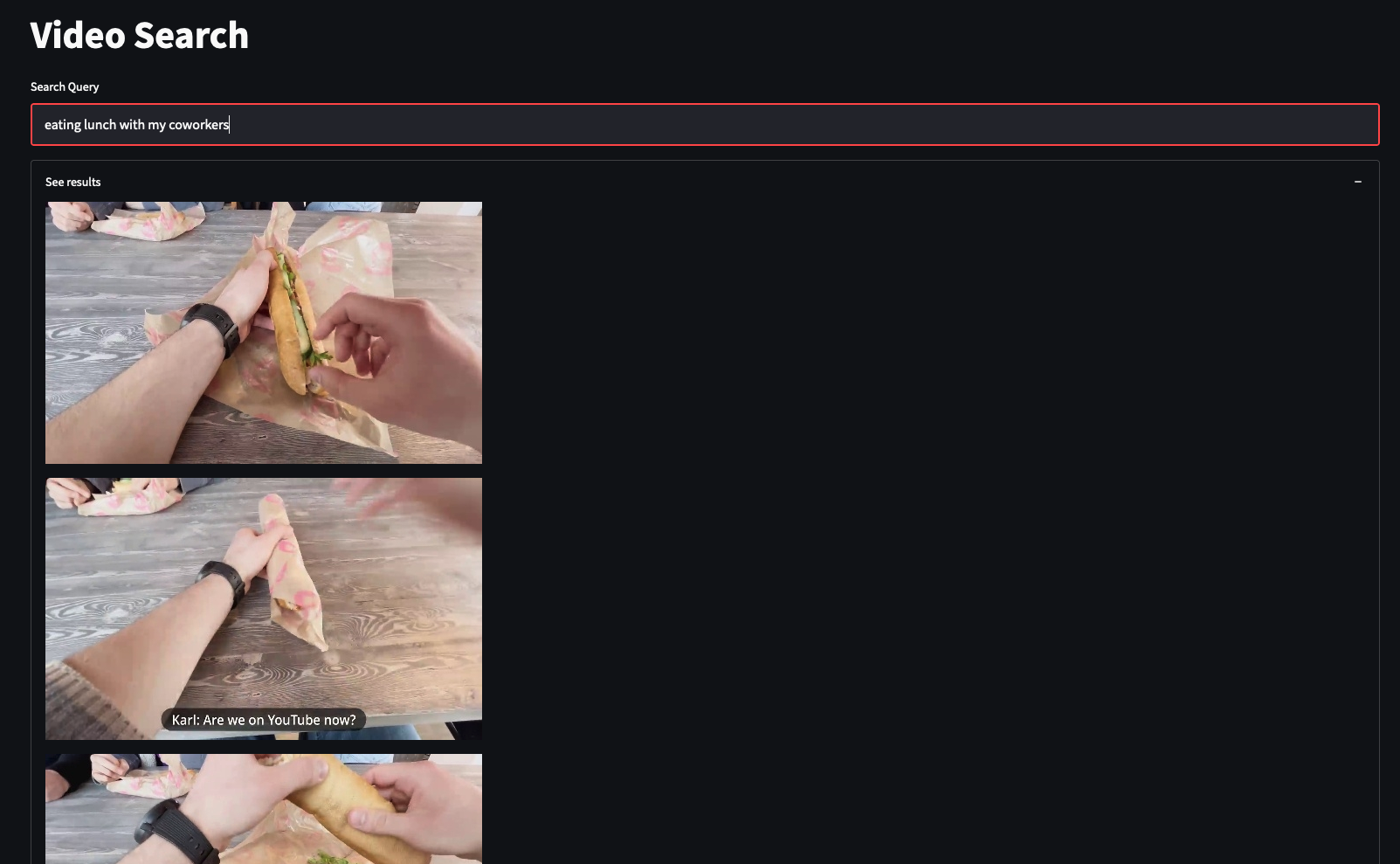

Video search for “eating lunch with my coworkers”

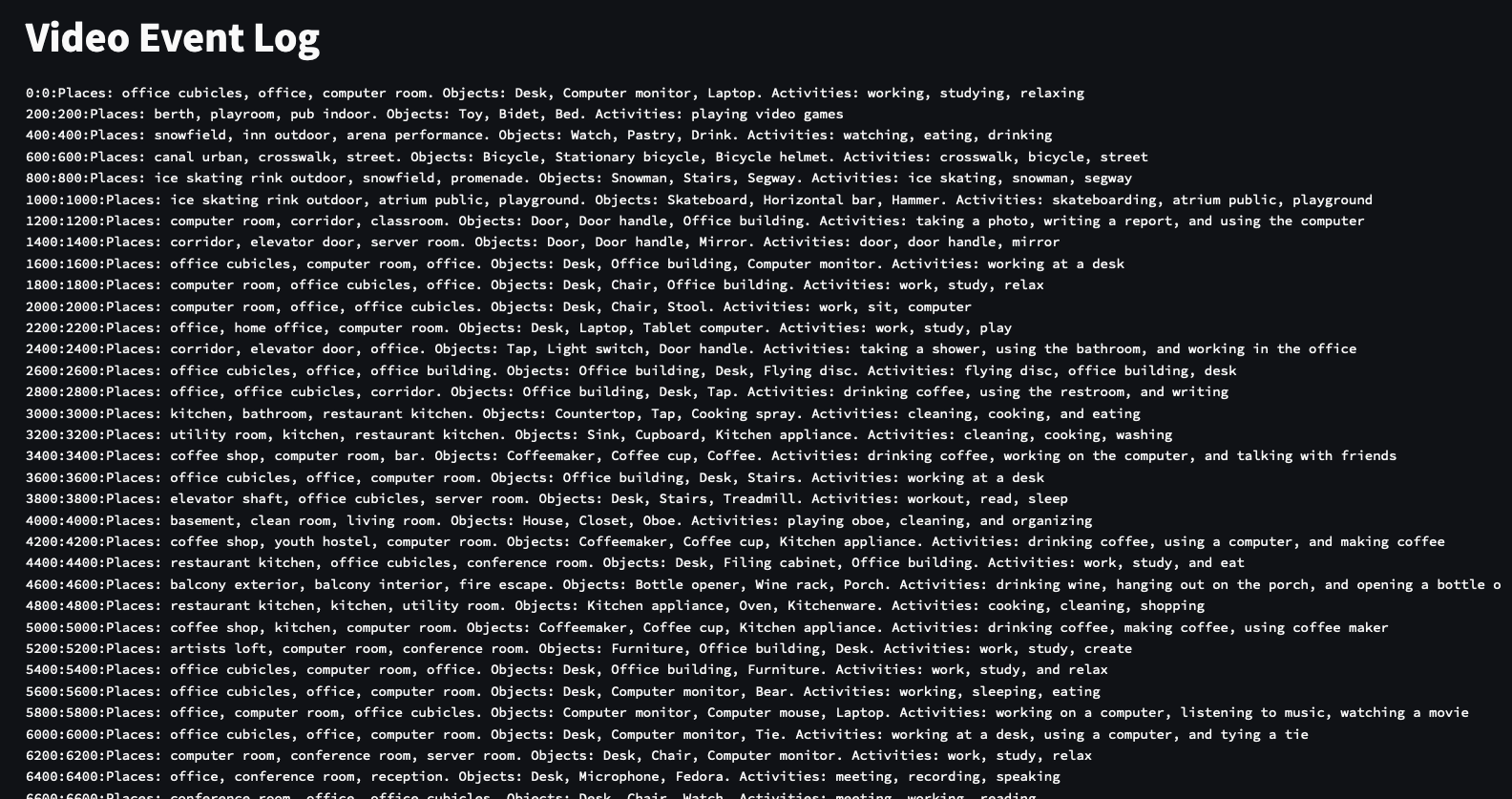

Next, I looked into producing an event log, with one line listing the places, objects, and activities seen in each frame in the video. The paper actually filters model output for places and objects by restricting possible answers to any of the places in the Places365 dataset and objects in the OpenImages dataset. This is a strategy I often use for controlling model output, but I followed the paper in not applying this restriction to the activities list, allowing for more expressivity from the model.

For each image, CLIP was used to rank the place and object categories and the top 3 for each are taken for the log. The LLM (I used T0pp after trying a few others like GPT-J) was then prompted to list the activities given those CLIP supervised descriptions. For example, I performed 1-shot learning and prompted T0pp with

Places: kitchen. Objects: coffee maker. I might be doing these 3 activities: eating, making breakfast, grinding coffee. Places: office cubicles, computer room, office. Objects: Desk, Office building, Computer monitor. I might be doing these 3 activities:

The results were definitely mixed. While there are clear examples of the log working as expected, T0pp may require more prompt engineering and definitely has less creativity than GPT-3 (by design).

Event log for egocentric video

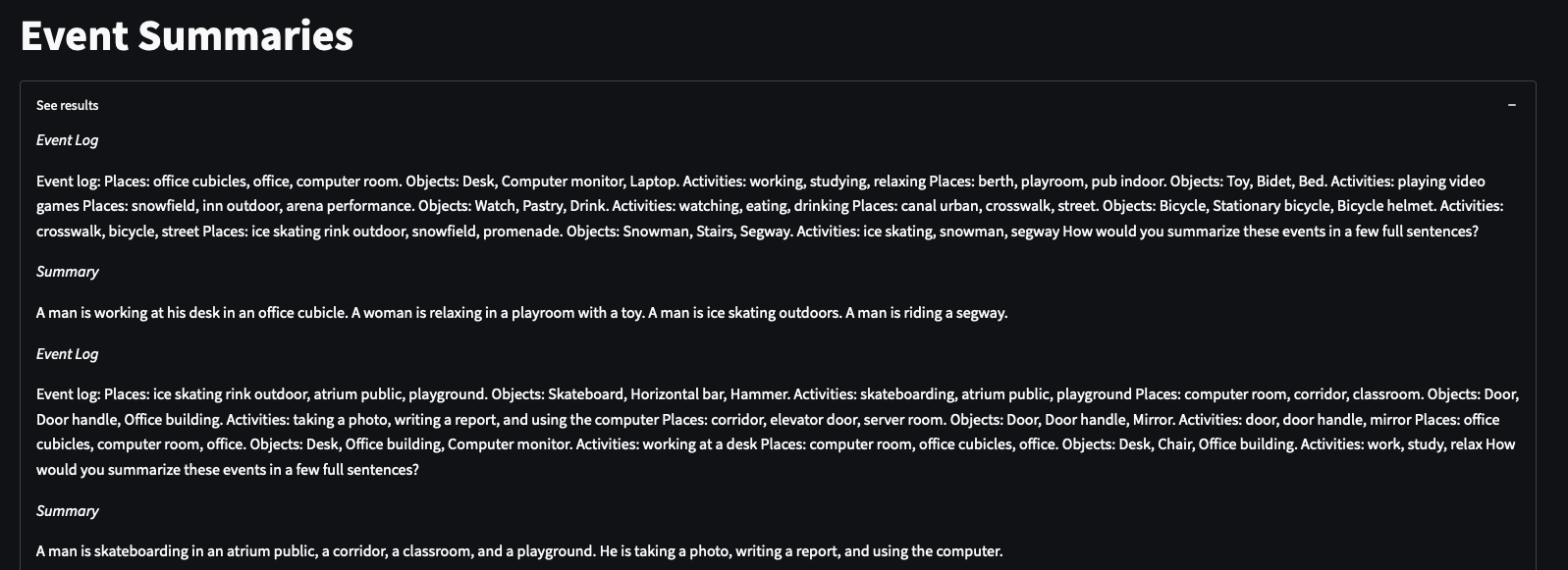

Finally, with the event log in hand, I explored creating event summaries. The paper makes it clear this is a challenging task, and it is easy to see why. We cannot feed the whole event log for the language model to reason over, so we must select a coherent segment to include in the prompt. But segmenting events from one another is no trivial task. The paper offers two solutions: uniform sampling or on the fly video search given specific events of interest. Given my limited compute budget, I tried the former with predictably poor results.

Event summaries

Errors tend to compound, so issues with the log generation only added more noise to the summaries. Nevertheless, I was impressed with what could be done with off-the-shelf models. With more time, finer sampling of video frames, and better prompt engineering, I feel confident that I could reduce the noise and produce a tighter result.

Conclusions

For me, the exciting thing about this paper is what is left to be explored. There is a whole universe of NLP companies focused on fine-tuning, and while GPT-3 is certainly impressive, it isn’t yet a replacement for producing reliable, consistent results for customers. Here is a truly viable alternative - flexible, controllable, recursively self-supervised. While costs in the short term might pose a barrier, many of these models are more lightweight than they appear and most can be accessed via API for a reasonable marginal cost. I’ll certainly continue to find ways to make this ensemble and embedding based approach useful for producing tangible value.