Demand Forecasting with Bayesian Methods

The Stanford Medical system sees a constant stream of patients through its doors every year, many of whom require intensive care. Blood transfusions are a common occurrence as part of a therapy or surgery, but blood platelets are a scarce resource that have a short shelf life. Therefore accurately predicting future demand is essential in order to minimize waste while ensuring hospitals have enough on hand for the current patient population. In 2017, Guan et al. published an initial model employing a frequentist approach, minimizing waste in a linear program with constraints that took patient features and current stores in account. This model was eventually rolled out into production in an open source R package titled SBCpip and currently serves the medical system.

I investigated two alternative Bayesian methods to predict demand more transparently: online regression and Gaussian processes regression. Bayesian models offer a number of key advantages over the current system. First, while the linear program approach outputs simple point estimates for the optimal inventory to have on hand, these Bayesian procedures generate a richer posterior distribution that can be used to quantify uncertainty and quantify how the model inputs impact predictions. Second, the data is messy and manually extracted into excel files, leading to duplicates and nonsensical values. The methods explored offer a higher degree of robustness to outliers, which can be tuned by varying the prior distributions. Third, since other hospital systems have similar blood platelet demands, there have been some efforts to generalize SBCpip to other facilities. The Bayesian approaches considered would allow models to lean more heavily on priors before adequate data has been generated and become more customized to each facility over time as data accumulates. Fourth, the linear program approach predicts demand indirectly, making results much harder to interpret. The methods proposed here allow for greater flexibility and transparency in diagnosing issues and determining the underlying drivers of a particular prediction.

Approaches

While the data cannot be made publicly available, there are a few key features to note. Our outcome variable, blood platelet units used, helps determine the best types of models to use for this problem. The amount used is a real valued number that closely follows a Gaussian curve, permitting the use of a rich class of normally distributed models. The regular fluctuations suggest that some seasonality may be present that could be picked up by a Gaussian process regression model given a suitable kernel. Below I consider some plausible Bayesian models that each have tradeoffs in simplicity, accuracy, and utility.

Online Regression

In a typical Bayesian regression problem, we have a setting with independent and identically distributed training data with future observations drawn from the same population. In this case we can simply place a prior over the weights and variance, evaluate the data likelihood and find the posterior through exact or approximate inference to determine a stable model from which we can make predictions. Here we are presented with a time series of features and inventory data and want our model to flexibly model trends that depend on our time step. Online regression is a naive baseline for this problem in which at time step t, we take the posterior from time step t − 1 as our prior and update the model using only the likelihood over the most recent batch of data. Define our original priors as \(p(\theta_0)\), then our model updates occur sequentially:

\[\begin{align*} p(\theta_{t}) = p(\theta_{t} \mid y_{t-1}, x_{t-1},\theta_{t-1}) &\propto p( y_{t-1}\mid x_{t-1},\theta_{t-1})p(\theta_{t-1})\\ p(\theta_{t+1} \mid y_{t}, x_{t},\theta_{t}) &\propto p( y_{t}\mid x_{t},\theta_{t})p(\theta_{t}) \end{align*}\]

While a simple regression may seem underpowered for this task, it provides an excellent baseline against which we can compare more complex approaches. The conjugacy of the Gaussian model makes it extremely efficient as we add new data points with easy interpretation. However, its failure to model dependency between data points may introduce bias that could be avoided with more complex approaches.

The model as implemented closely follows the approach outlined in Christopher Bishop’s Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning. Given model \(y_i = w_ix_i^T + \varepsilon_i\), we give likelihood and prior distributions as \(p\left(y_{i} \mid x_{i}, w_{i}\right)=\mathcal{N}\left(w_{i} x_{i}^{\top}, \beta^{-1}\right)\) and \(p\left(w_{0}\right)=\mathcal{N}\left(m_{0}, S_{0}\right)\) respectively, where \(\beta\) is a precision hyperparameter, \(m_0 = \mathbf{0}\) and \(S_0 = diag(\alpha^{-1})\) for hyperparameter \(\alpha\). Our posterior is analytically derived as \[\begin{align*} p\left(w_{i+1} \mid w_{i}, x_{i}, y_{i}\right)=\mathcal{N}\left(m_{i+1}, S_{i+1}\right)\\ S_{i+1}=\left(S_{i}^{-1}+\beta x_{i}^{\top} x_{i}\right)^{-1}\\ m_{i+1}=S_{i+1}\left(S_{i}^{-1} m_{i}+\beta x_{i} y_{i}\right) \end{align*}\]

For model criticism, Bishop recommends evaluating the marginal likelihood, or model evidence, which he derives analytically. For M features and N observations, the log marginal likelihood can be expressed as \[\begin{align*} \log p({y} \mid \alpha, \beta)=\frac{M}{2} \log \alpha+\frac{N}{2} \log \beta-E\left({m}_{N}\right)-\frac{1}{2} \log \left|{S}_{N}^{-1}\right|-\frac{N}{2} \log 2 \pi \end{align*}\] Therefore we can directly use this expression to select for optimal hyperparameters \(\alpha,\beta\) to improve the model fit.

Gaussian Processes Regression

I look to Gaussian processes (GP) regression to correct for the deficiencies of the regression model. While the prior model considered datapoints to be independently drawn from a stationary distribution, Gaussian processes explicitly model the covariance relations between time steps. Here we consider our feature vectors \(x \in R^d\) over T time steps \(x_1,...,x_T\) and each observation of inventory used \(y_i = f(x_i)\). If we assume the functions \(f\) to be given by a prior Gaussian process \(f \sim GP(\mu, K)\) for some mean \(\mu\) and covariance matrix \(K\) and \(y_i \sim N(f(x_i), \sigma^2)\) then we obtain posterior \(p\left({f} \mid x_{n}, y_{n}\right) \propto {N}\left({f} \mid {\mu}^{\prime}, {K}^{\prime}\right)\) for \({K}^{\prime}=\left({K}^{-1}+\sigma^{-2} {I}\right)^{-1}, \; {\mu}^{\prime}={K}^{\prime}\left({K}^{-1} {\mu}+\sigma^{-2} {y}\right)\). Similarly, we can obtain an exact posterior predictive distribution given by \[\begin{align*} y_{T+1} | x_{T+1}, x_i, y_i &\sim N(m_{T+1}, v_{T+1}) \\ m_{N+1} &=\mu\left({x}_{N+1}\right)+{k}^{\top}\left({K}+\sigma^{2} {I}\right)^{-1}({y}-{\mu}) \\ v_{N+1} &=K\left({x}_{N+1}, {x}_{N+1}\right)-{k}^{\top}\left({K}+\sigma^{2} {I}\right)^{-1} {k}+\sigma^{2} \end{align*}\]

GP regression offers additional modeling decisions that improve its attractiveness for our use case. First, there are a variety of potential kernels for expressing the relationship between feature vectors over time. Our choice determines how closely we model regular periodicity and linear trends in the data.

Additionally, since GP regression is closely related to time series methods like ARIMA, we can eschew using features at all and treat the blood inventory as a standalone data series. Why might we prefer this approach? The other regression approaches obtain a posterior predictive distribution by conditioning on \(x_{N+i}\) for \(i \in [1,7]\), feature vectors which are supposed to contain data like patient counts and other measures that aren’t actually available for future days. While features could be extrapolated from current data, a GP regression approach can condition simply on the time step and avoid some of these messier modeling decisions.

Experiments

Over the experiments run, the simple online regression obtained the lowest mean absolute error across 1, 3, and 7 day prediction intervals. This result is somewhat surprising given the difference between the modeling assumptions (eg. independence) and the true data generating process but can be reconciled when we consider that we limited GP regression’s performance by limiting the features used in fitting. While online regression achieved the best results under the evaluation metric, GP regression may still be preferable in a practical setting. Comparing the mean absolute error among the methods explored:

\[\begin{array}{l|cccc} Model & MAE\, 1\, Day & MAE\, 3 \,Day & MAE\, 7 \,Day\\ Online Regression & 6.40 & 6.65 & 6.58 \\ GP Regression & 7.33 & 7.80 & 7.89 \end{array}\]Online Regression

The regressions were tested under two scenarios: for each time period, we could either fit the model using data since inception or look back over a fixed window. The data since inception approach was too constraining and performed slightly worse in evaluations, leading the fixed window approach to be used for comparisons. The model was fit over 7 day increments and produced predictions for 7 days into the future.

We can understand the performance of the model by looking at the results more closely. First, while the online regression approach does not explicitly model a time series, one-hot encoded day of the week features are included as input to the model. Therefore it still can capture some of the cyclicality of blood platelet demand.

The online regression was fit over a grid of potential hyperparameter values for \(\alpha, \beta\), with the model with the highest marginal likelihood selected for final predictions. It was sensitive to extreme values of each hyperparameter, but otherwise relatively robust to misspecification within a neighborhood of values.

Gaussian Processes Regression

GP regression offers a variety of modeling decisions, but perhaps the most important is the choice of kernel. This decision directly impacts the model’s ability to reflect the true relationship between observations. In “Automatic model construction with Gaussian processes” David Duvenaud outlines a decision process for choosing the best kernel given a dataset. I experimented with permutations of additive kernels, combining Exponential Quadratic, Linear, Periodic, and Locally Periodic varieties. The Locally Periodic kernel was of particular interest as the data shows consistent day of the week seasonality but with magnitudes that vary over time.

The model was fit in TensorFlow Probability by maximizing the marginal likelihood of the model parameters and the observation noise variance over the training data via gradient descent. The GP regression model was then fit on the data using the optimized kernel before posterior samples were drawn. Over all kernel experiments, a combination kernel of Exponential Quadratic and Locally Periodic varieties produces the best results.

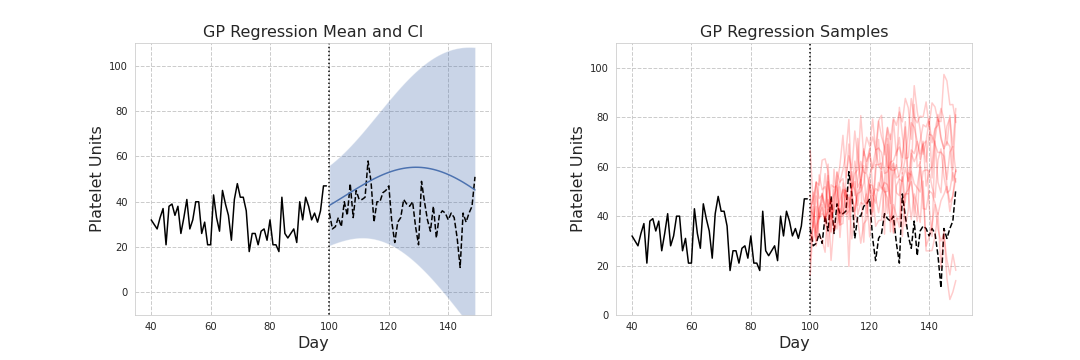

Left: Mean and credible intervals drawn from the posterior predictive distribution. Right: sample paths drawn from the posterior predictive distribution.

The model was then fit for periods increasing in 7 day increments from the data series inception, with predictions made for the following 7 day increment. For example at day 100, data from days 0-100 are taken as the training set, with the mean and standard deviation from the posterior predictive distribution forming confidence intervals for the prediction period. Alternatively, samples could be drawn from the posterior predictive distribution to simulate different paths created by the Gaussian process.

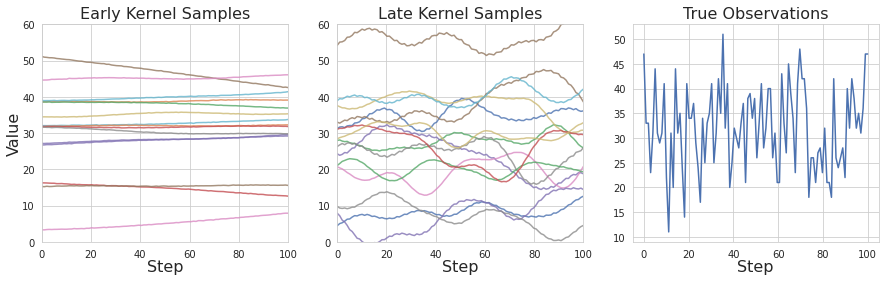

Left: Samples drawn from an Exponential Quadratic / Locally Periodic kernel with parameters learned from fewer than 100 datapoints. Middle: The same kernel with parameters learned from all datapoints. Right: First 100 observations of platelets used.

We can make further sense of GP regression’s underperformance by looking at the kernels learned themselves. Comparing kernels fit in the training process along with the true observations, we can see that given little data, the kernel is unable to adapt to the variation in the data. A kernel with parameters trained on the full dataset shows much more reasonable variation, with both global and local trends. However, comparing this kernel to the observed variation, we can see it still has a long way to go to match the ground truth. Additional data would go a long way to improving this method, but there may also be more expressive kernels than those explored that could drastically improve performance.

While the hyperparameter search was partially limited by compute time, GP regression’s results indicate the method could show promise in this application. While it achieved higher error than other methods, its performance could improve if we included additional features, some of which might be known ahead of time by hospital administrators. Additional variance control, such as full marginalization of the model’s hyperparameters, would also increase its effectiveness.

Conclusions

I took a survey approach to understanding the tradeoffs among Bayesian methods for resolving a difficult, real-world problem. Forecasting in general is a daunting task, since it requires extending a model beyond the domain of observations seen. In the medical setting, it is even more crucial to have humans in the loop, and while the original linear program could set hard boundaries on the predictions produced, it is more useful to ensure that end users have an intuitive understanding of the results produced and the tools to probe alternative outcomes.

The Bayesian methods explored each had significant problems in completely satisfying the objectives set out in the introduction, but the approaches could be considered a starting point for additional refinement. In particular, GP regression’s ability to generate sample trajectories and credible intervals could prove valuable for those in charge of inventory ordering decisions. Quantified uncertainty can be vastly superior to relying on heuristics.

Finally, the experiments made clear that the data may not contain sufficient information for more exact predictions. Some effort should be expended to encourage the medical system to maintain more expansive records, enabling models to find the best features that drive blood platelet demand.